MEDIEVAL MIDDLE EASTERN DIETETICS

I’ve always had an interest in Medieval Middle Eastern cooking, having spent the last couple of months in Egypt I have been doing some further research on the historical relationship between food and science in the Middle East.

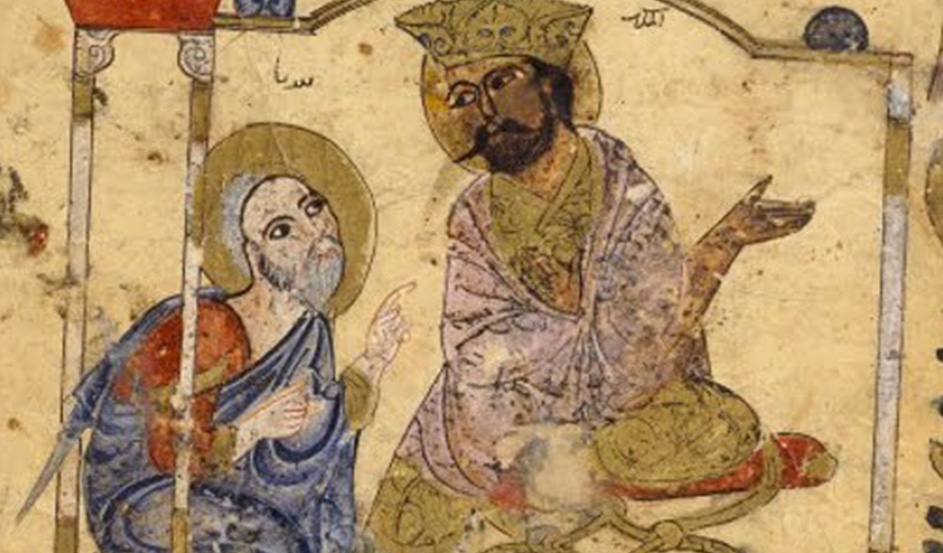

Arabic medical writing started in the early 8th century during the creative and dynamic formative period of the Islamic community. Many Greek medical works including the Hippocratic Corpus and those of Galen were translated into Arabic, many works of lesser ranking figures such as Rufus of Ephesus (first century AD) survive only in Arabic translation.

The openness to Greek science shown by both the translators and their patrons was motivated from the start by an active and witting search for solutions to pragmatic problems.

Parallel with the activities of both the translation movement and the first original efforts of medical writers were signs of an emergent high culinary tradition expressed in Arabic and centred in Baghdad. The earliest extant culinary manual, Kitdb al-tabi-kh, compiled Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq (of whom nothing is otherwise known) belongs to the late tenth century although it contains evidence of a high culinary culture dating from the early ninth century.

An interest in gastronomy appears to have been a pastime of various patrician personalities, including several princes of the ruling ‘Abbasid house.

The activity then spread among the bourgeois sectors of urban Muslim society, creating a “great” written cooking tradition in Arabic distinct from the unrecorded practices of the working-class population, both urban and rural.

While this may have all the appearances of a gastronomic “new wave”, it is more likely to have been a revival of what was, perhaps, the oldest high culinary tradition in history. Some recipes have the same concise, formulaic style of those found in Apicius (a collection of Roman cookery recipes).

The link between the culinary tradition reflected in al-Warraq’s compilation and the Sassanian (or earlier Persian) past is evident in the number of dishes and ingredients with Persian names. What is nevertheless clear from this brief survey is that the Arab-Islamic medico-culinary tradition is founded upon the twin bases of Greek humoral theory on the one hand and the indigenous culinary practices of the ancient Near Eastern cultural centres on the other.

Al-Warraq’s is but one of half a dozen Arabic culinary manuals (edited and published to date) dating from the tenth to thirteenth, fourteenth centuries whose provenances range from Iraq to the Iberian peninsula.

Together they comprise a treasury of several thousand recipes reflecting the enormously rich and varied culinary cultures of the medieval Muslim Middle East.

Al-Warraq shared many traits with other cookbook compilers, although he alone included poetry. Despite his claim to have compiled recipe of dishes prepared in court circles, the contents of his work reveal a far wider scope of interest. They embrace the tastes of a broader urban bourgeoisie. In some cases, simple preparations of rural origin were transformed in the urban context, chiefly by the addition of more expensive ingredients; regional variations of a particular dish are also found.

Al-Warraq’s compilation like other culinary manuals, reflected a close awareness of contemporary medical views on dietetics. Several of the opening chapters deal with subjects reflecting the influence of the Greek dietetic tradition. In a later collection of recipes, dating from thirteenth- or fourteenth-century Egypt, such information is diffused throughout the book, where comments on the benefits of a particular dish are often included along with the recipe itself.

‘Abd al-Malik b. Habib (d. 853). Born in al-Andalus, he practised as a jurist in Cordobafollowing a three-year sojourn in Egypt and Mecca where, among his other activities, he gathered material for a medical compendium in which he dealt with the cure of illness and the preservation of health chiefly by means of food and diet.

All of this illustrates a dialogue between medical professionals and laymen in medieval Islamic culture, each group to some extent informing and being informed by the other. The culinary manuals provide a clue to the nature of this relationship. They point to the central place of the domestic household in the life of the leisured urban class in Islamic societies, where not only proper nourishment could be provided to its members but also remedies for minor ailments or disorders which did not initially, at least, require the physician’s expert knowledge of drugs to combat more serious disorders.

“Medieval Arab Cookery” by Charles Perry takes a much more in depth look at this topic and English translation of al-Warraq’s “Kitb al-tabi-kh”.