FLAVOUR NETWORK AND PRINCIPLES OF FOOD PAIRING

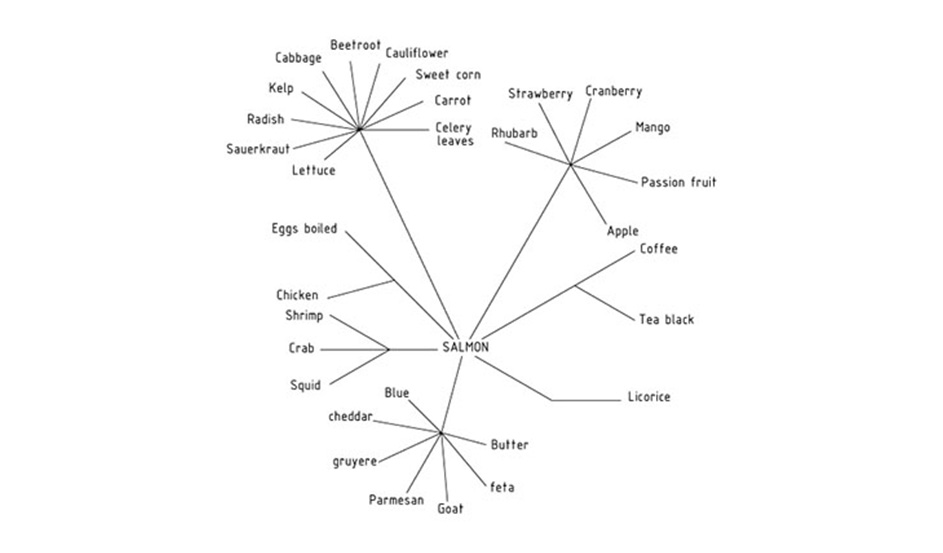

Some years ago, while experimenting with salty foods and chocolate, chef Heston Blumenthal discovered that white chocolate and caviar taste rather good together. To find out why, he had the foods analyses and discovered that they had many flavour compounds in common.

He went on to hypothesise that foods sharing flavour ingredients ought to combine well, an idea that has become known as the food pairing hypothesis. There are many examples where the principle holds such as cheese and bacon; asparagus and butter; and in some modern restaurants chocolate and blue cheese, which apparently share 73 flavours. But whether the rule is generally true has been hotly debated.

Today, we have an answer thanks to the work of Yong-Yeol Ahn at Harvard University and a few friends. These guys have analysed the network of links between the ingredients and flavours in some 56,000 recipes from three online recipe sites: epicurious.com, allrecipes.com and the Korean site menupan.com. They grouped the recipes into geographical groups and then studied how the foods and their flavours are linked.

Their main conclusion is that North American and Western European cuisines tend towards recipes with ingredients that share flavours, while Southern European and East Asian recipes tend to avoid ingredients that share flavours.

In other words, the food pairing hypothesis holds in Western Europe and North America. But in Southern Europe and East Asia a converse principle of antipairing seems to be at work.

Ahn and co also found that the food pairing results are dominated by just a few ingredients in each region. In North America these are foods such as milk, butter, cocoa, vanilla, cream, and egg. In East Asia they are foods like beef, ginger, pork, cayenne, chicken, and onion. Take these out of the equation and the significance of the group’s main results disappears.

That backs another idea common in food science: the flavour principle. This is the notion that the difference between regional cuisines can be reduced to just a few ingredients. For example, paprika, onion and lard is a pretty good signature of Hungarian cuisine.

Ahn and co’s study suggest that dairy products, wheat and eggs define North American cuisine while East Asian food is dominated by plant derivatives such as soy sauce, sesame oil, rice and ginger.

Ahn and co conclude by discussing what their network approach can say about way recipes have evolved. They imagine a kind of fitness landscape in which ingredients survive according to their nutritional value, availability, flavour and so on. For example, good antibacterial properties may make some spices ‘fitter’ than others and so more successful in this landscape.

Others have also looked at food in this way but Ahn and co bring a bigger data set and the sharper insight it provides. They say their data contradicts some earlier results and that this suggests that better data is needed all round to get a clearer picture of the landscape in recipe evolution.

Given the number of ingredients we seem to eat, the total number of possible recipes is some 10^15 but the number humans actually prepare and eat is a mere 10^6. So an important question is whether there are any quantifiable principles behind our choice of ingredient combinations.

Another intriguing possibility is that this kind of evolutionary approach will reveal more not just about food, but also about the behaviour of the individuals that created it.

Food pairing seems to be one principle operating in some parts of the world. How far antipairing can take us has yet be seen, although customers to the Blumenthal’s restaurant, The Fat Duck, may be among the first to find out.

The whole paper “Flavour Network and Principles of Food Pairing” is available here

Also visit Food Pairing website

This article is from Technology Review